Six weeks ago I left Brixton. It wasn't an eviction: Clifton Mansions is still going, and will probably last the summer. For the first time I chose to leave of my own accord. A tedious, convoluted story: contradictory promises were made by the former resident. There was a dispute who has the 'right' to No. 19, and for how long. The ambiguous, unwritten rules of squatters' ettiquete were invoked and challenged. For me all this didn't matter much: I don't believe in rights. I was living in no. 19, and I could have stayed. But I chose to give it up.

Through all my squatting years, Clifton Mansions stood as a distant haven. During three years I moved house 9 or 10 times. Eviction, disruption, excitement, despair: all this time I knew that the fortunate Clifton residents were safe from the cycle. The Mansions were stable: the court case dragged for years. Of the problems I knew well: the flats were freezing cold in winter and too hot in summer. Lack of light. The buildings were badly built and badly maintained. The hassle of the drug dealers in the yard; the noise. All these seemed a price worth paying. I thought of it as Camellot, a safe castle standing wrapped in misty winds.

Three months of living there had driven the mists away; things stood clearer. Strangely, the romantic image remains, alongside the real experience. These are fragments of a belated farewll.

* * *

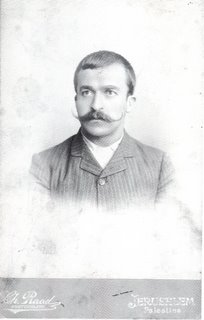

When I grew up there were hardly any black people in Israel ; Ethiopean Jews came first in the 1980s, and were still much of a curiosity (now there's more of them). Living in an area where about half the people are black was therefore a new experience. It is one thing to think of yourself as free from racism; it is quite another thing to put it to a daily test. Racism lives in our heads, whether we want it or not: it's too deep in our culture(s) to pretend that it can driven away simply by ideals. When I first lived in Brixton - three years ago - I found my own racism, in the way I looked at people, in my body reactions. Partly it was the fear of the Other, the one who looks different; and partly it was things I heard and read in books and films, that have become part of my unconcious. Brixton gave me a chance to confront these notions in my head, and to rid myself of them as part of a daily experience.

Yet 'a black neighbourhood' is a misleading generalization. There is a big difference between the African community and the West-Indian. The Jamaican community is the domminant in Brixton, culturally and economically. I like the way rastafarians are so outrageously loud and direct. I like the way everybody waves to eachother on the street. There is a sense of a living place, that I rarely find in other parts of London. But there were also things I didn't expect, like aggressive male-chauvinism and homophobic attitudes. I know too little to make generalizations. But the incidents which I witnessed surprised me - not only because the men involved were abusive - but also the sense of rightousness that they had. There was something almost religious about it.

* * *

'I'm sick of Brixton, all the drug-dealers...' yes there is a lot of drug-dealing happening, and it's often a shorthand for all things nasty and unpleasant. But why are drug dealers worse than other dealers? I think more should be said.

If you are walking down Brixton Road and Coldharbour Lane in the evening you will be offered skunk every two meters. Now I don't like skunk and more so I don't like to be offered stuff to buy when I walk down my street. I don't care much if it's giant billboards selling shampoo or people pushing drugs shouting in my face: it's the same thing, unsolicited attempts to catch my attention in order to make profit. I think black people don't get hassled the same way. But as a white person walking down Coldharbour Lane I was assumed to be someone on a night out, a customer. I resented it. I was just walking home.

Crack is a serparate mileu, traders and clients. There was a crack dealer living in the courtyard. He was high on it half the time himself, just sleeping on the couch in the middle of the day, dumb and numb. Other times he would sweep the courtyard and burn incense sticks. He was harmless. His customers were erratic miserable junkies, who I didn't know and didn't care to know. I could hear them in the yard at night, pissing and swearing and arguing. Their lifestory is probably sad and horrible but I wanted to keep out of it. It is not pleasant to go out of your door and see someone smoking crack hidden behind the bins. The smell is foul.

I never felt at serious risk. The problem wasn't fear, but the notion that you have to be constantly careful and aware of the people around you. That you have to brace yourself before leaving home, before stepping out to the street. That step of relief when locking the gate behind you. It gets tiring very soon.

* * *

One of the signs of gentrification is trendy places opening up, bars and cafes, organic food shops. Not all of these are yuppie and soul-less. I can be sarcastic about these things but I like good food and it's nice to have a variety other than workers-cafes offering full-english-breakfast. Of these places I liked best the Ritzy. Drinking Jappanese beer overlooking townhall square, Brixton feels cool and viberant and diverse. But when you step back into Coldharbour Lane you till bump into crackheads and crazy people muttering FUCK FUCK FUCK. Brixton's gentrification seems less uneven than the usual: a lot of kicking and screaming involved.

But the more disturbing side, for me, is the club scene, Brixton's status as a cool place to go out. It thrives on the dodgy reputation of the area. This 'edgy' character brings in money, people from richer parts of town looking for a dose of excitment on the weekend. While in King Cross e.g. the dangerous image (drugs and prostitution) is a 'problem' to be 'solved' through regeneration, in Brixton it's too much part of the story to tackle. There is a feeling of sponsored edginess - that too much money is being made - that I find disgusting.

* * *

My favourite part of Brixton was and remains the Market. Fruits and Veg I get from elsewhere, so I would go there for other things: Syrian pickles in the Persian shop, Turkish bread in the Portugese one. But I loved the noise, I love the old ladies with their baskets and trolleys. And I love going there at night, cycling through electric Lane, when all is dark and quiet, dodging the holes in the road and thd dirty water puddles. In my head I can hear the noise of the daily market that died only a few hours ago (the Carribbean music, the cheesy Indian pop tunes) and this makes the silence tactile, like a pause in a conversation. Alive, only sleeping.