It's Friday, the day before new year's eve. You cycle through the supermarket's car park, hectic with shoppers and reversing cars. Carefull, they can't see you in this weather. You get off your bike, and walk it through the small gate at the end of the car park. Down the slope, look left for cars, then get on your bike. You're in the market.

It's half past eleven. Probably too late for the Organic place. They usually leave leftover bags outside but you can't see any. Just to make sure you cycle up to the skip: here they are. Four bags of organic produce. 'Luxury vegetables'. Another two deep inside the skip but you're not going to jump in. It's too risky and you're on your own today. Four bags are fine. Don't be greedy now.

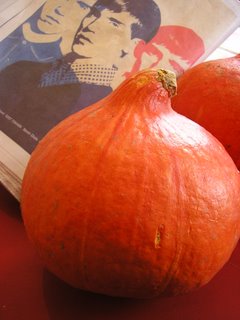

You pull the bags out of the skip and put the vegetables in your panniers. Mostly root vegetables; at last, something seasonal. Swedes and parsnips: you didn't know these vegetables existed before you came here. There's no words for them in your mother tongue. The best find: seven orange squashes. What will you do with seven squashes? roast them with potatoes; make Moroccan pumpkin and yellow split peas soup; couscous with pumpkin and dried apricots. And you can always give some away.

It's raining and it's cold. But you don't mind. You like skipping in the rain. There's something calming about it. The waterproofs keep you dry and there's not too many people around. You carry on.

The mushroom place: nothing there. A van uploading some stuff. 'Don't touch it!' a man shouts at you. You wave to say ok no problem. 'Don't touch it I said!' you cycle away. Touch what? And why would you want to take his vegetables, when so much is thrown away? over there, right next to the bins, a stack of boxes of yellow peppers. Some of them bruised but most are fine. Roasted and marinated. With a bit of balsamic vinegar.

Not much else. They must have finished earlier today. You didn't find much fruit, but slowly the cold is getting to you. You turn the bike and start heading out of the market. But there you spot another stack of boxes. They turn out to be red grapes from Peru. What's wrong with them? one or two mouldy grapes in each bag. You take six bags. You don't need more. That will get you through the New Year.

On the way back home, you think of wasted food.

* * *

Strangely, the taboo on throwing away food seems to hold in our society. You don't have to be a poor kid to be told not to waste food. Good boys, rich or poor, finish their plates. This is why the sight of heaps of good vegetables and fruits in a skip is so infuriating. The thought that what could feed people finds its way to a landfill would make almost anyone uneasy.

But the waste of fresh produce is just the tip of the iceberg, and I'm not talking about lettuce now. It's the icing on this 4-layers wedding cake of waste: (1) the wasted labour of the people who planted the vegetables, harvested them, packed them and shipped them. Many hours of sweat and hard work for pittance-wages in far away places (2) the wasted energy and water involved in growing the produce (3) the wasted fuel required to bring the figs from Turkey and the mangoes from Brazil. I think most of the stuff is imported by air. The gas for their trip from the harbour to London (4) packaging and wrapping, the palletes and boxes - mountains of nylon, plastic, metal and wood, that find their way to the skips as well.

It is these invisible layers of waste that are the real problem. The wasted fruit and veg may be absurd and ludicrous and sad. But it is the wasted human sweat and oil and electricity, the polluted air and seas, which make this project a disaster. Just imagine what would happen if all the world was living so wastefully. How long could the planet take this?

Waste is not an unfortunate byproduct of the global market. It is no accident. Importing most of your fruit and veg from overseas will inevatably involve large volumes of waste. But the point is that waste is not bad for this sytem; it's what makes it tick. If the core principle could be summarised as 'produce something more than you need, as cheaply as you can; try to sell it for the highest price' then really if your product goes to the bin that's great because you can sell another one. Waste is good, as long as it encourages consumption. The less careful the consumer the better; that's why 'spontaneity' is considered such a good thing. That's why an atomized society is so good. The logic of sharing, saving, mending, conserving, and re-using is obscene to a system based on short-term profit. When was the last time you saw someone carrying a 10kgs bag of rice on the tube home? A sight so familiar in third-world countries. They don't buy rice by the half-kg over there.

You've been coming to the market for three years, and you still can't get it. When you find so much of something - tomatoes or plums - you want to take it all, conserve it, pickle it, make jam from it, fill the kitchen with jars, so it will last for a while. But what's the point in pickling and conserving, when you'll be in the market next week, and find some more. Because there's always more. Much more than you could possibly take. Sometimes you feel the market is playing tricks on you; it ridicules your fallacious attempts to make sense and do right in an ocean of madness.

She didn't understand what the whole thing was, until someone told her she was standing outside Jack Straw's, the Foreign Secretary's house

She didn't understand what the whole thing was, until someone told her she was standing outside Jack Straw's, the Foreign Secretary's house